By Kat Kan, MLS

Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month is observed every May. This year, I felt it was more important than ever to celebrate and uphold our cultures in the face of overt racism and actual physical attacks upon people of Asian and Pacific Islander descent, which occurred throughout 2020 and have continued into 2021. Specifically, I want to focus on the positive impact AAPI comics creators have made with the books they’ve published.

When I started thinking about AAPI contributors to the world of comics, a flood of names came quickly to my mind: Stan Sakai, Gene Luen Yang, Lynda Barry, Mariko Tamaki, Jillian Tamaki, Amy Chu, Greg Pak, Rina Ayuyang, Mari Naomi, Derek Kirk Kim, Fred Chao, Amy Chu, Kazu Kibuishi, Kean Soo, Robin Ha, Trung Le Nguyen. I was inspired to search further and uncovered a lot of information that was new to me.

But before I share details about the individual lives and contributions of AAPI authors and artists, I’d like to provide a little history. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Asian Americans found themselves the unfortunate targets of virulent stereotyping and scapegoating, in a way that parallels what we’re seeing today. But whereas the current animosity stems largely from the COVID pandemic, which originated in China, a different set of circumstances influenced anti-AAPI sentiment of generations past.

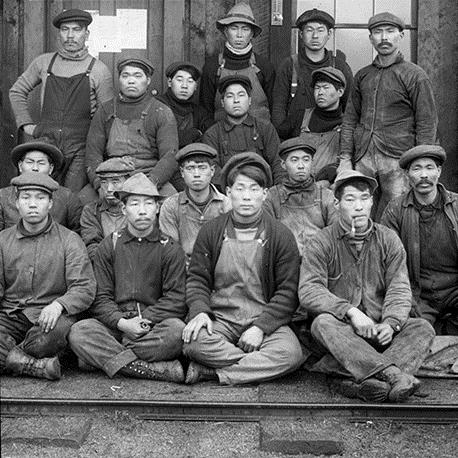

Chinese people first started coming to the United States in large numbers during the 1850s to work as laborers in mines, farms, and on fishing boats, and to help build railroad tracks in the American West. From the beginning, White Americans resented these foreign laborers. By the 1870s, newspapers were carrying stories about the “Yellow Peril.” Laws were passed—especially the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882—to restrict Chinese immigrants’ civil rights, access to education, ability to work, and even freedom to express their culture. This act was the first federal law targeted to restrict the rights of a specific ethnic group.

At about this same time, sugar plantation owners in Hawaii began to entice the Japanese to come to Hawai’i and work on their plantations. Some of those Japanese workers later left Hawai’i and traveled to the West Coast. Some took to farming the very poor quality land that Americans were all too glad to sell, until they saw how the Japanese started using their farming methods to produce bountiful crops. Those who stayed in Hawaii started families; some—including Hideichi Takane, my husband’s maternal grandfather— undertook unionizing efforts to improve their working conditions. Predictably, this was met with resistance from the plantation owners. My grandfather actually had to hide in the jungle to avoid being arrested or killed.

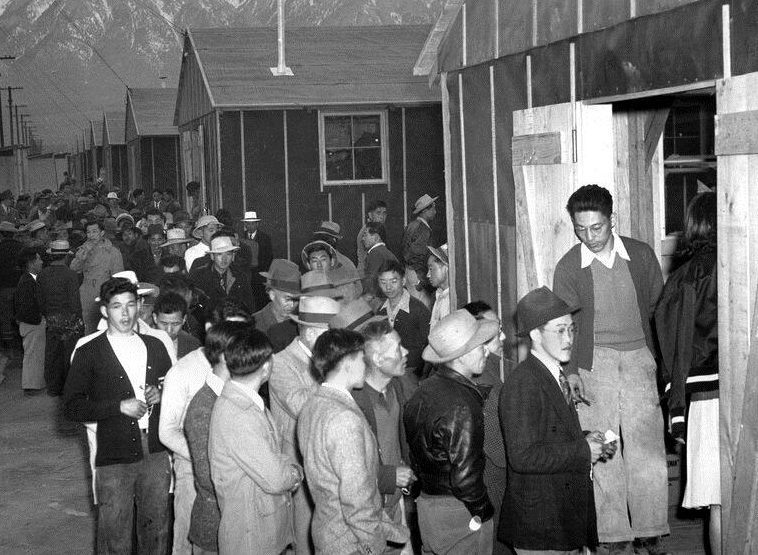

When the Japanese Imperial military bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, many Americans turned their rage at the attack towards all Japanese Americans, including the Nisei—second-generation Japanese who were born in the U.S. and were therefore legitimate American citizens. More than 120,000 Japanese living on the West Coast were forced into internment camps for the duration of the war (Kiku Hughes’ graphic novel “Displacement” shows readers how the Japanese had to live in these camps). With only a few exceptions, most of their property was taken from them and never returned. At President Roosevelt’s orders, the FBI investigated, but not a single Japanese American was ever convicted on a charge of spying for the Japanese government. Hawaii, at that time a territory of the United States, was put under martial law for the duration of the war.

Despite this naked animosity directed towards people of Japanese descent, early in 1942, the U.S. government realized it needed more men to enlist in the Army. So recruiters went to the relocation camps and to Hawai’i and asked for volunteers. Many did; most of the males in my father-in-law’s high school class of 1942 enlisted in the Army, including one Daniel K. Inouye. Many of these young men joined the new 442nd Regimental Combat Team, part of the 100th Battalion, an all-Nisei combat battalion. Some Nisei refused to declare their loyalty to the U.S., along with some of the Issei (first generation Japanese Americans); most of these were in relocation camps. They included George Takei’s parents, as he recounts in “They Called Us Enemy.”

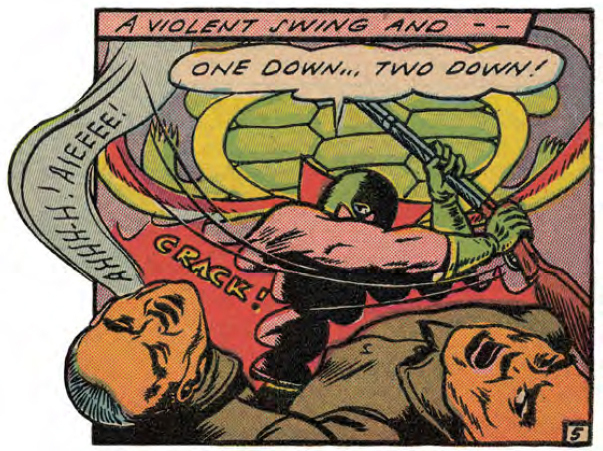

Almost from the beginning of Asian immigration to the U.S., Chinese and Japanese were portrayed in editorial cartoons as grossly exaggerated caricatures with slanted eyes and leering expressions. American comics published during World War II continued to portray the Japanese as evil caricatures. Even after the war, this practice continued in entertainment media.

Decades after World War II, anti-Asian attitudes persisted. One very notorious event was the murder of Chinese American Vincent Chin by a couple of Detroit auto workers who were angered by what they perceived as Japanese encroachment upon the U.S. automobile industry. Even as recently as 2016, I personally had to deal with anti-Asian comments and actions from students in the Roman Catholic school where I was the school librarian (they knew I’m half Japanese). Then in early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic ushered in the most recent wave of anti-Asian discrimination, with thousands of violent attacks on Asian Americans—not only Chinese, but also Japanese, Thai, Vietnamese, Filipino, and other ethnicities.

These conditions all contributed to difficulty AAPI people continue to experience on a macro level in their quest to be regarded as true Americans. AAPI people have struggled to be respected and accepted in their professional lives as well—as mirrored in the world of comics.

Now back to the topic!

Given all this unfortunate historical backstory, I decided I wanted to find out who the first AAPI comics creator in the U.S. was. The person I identified was Larry Hama, whom I remember from the “G.I. Joe” Marvel Comics series, which he started in 1982 (I bought lots of those for my older son back in the day). Thinking of Hama reminded me of a Chinese immigrant named Cy Young, who worked as a Disney animator on such films as “Snow White,” “Fantasia,” and “Bambi.” Another Chinese American, Tyrus Wong, also worked on “Bambi.”

I figured there must be many more people I was not familiar with, so I discussed my search with one of my co-workers as we shared Information Desk duty one day. She took to the challenge and began researching on her own. She soon discovered Chu Fook Hing, who wrote and inked a comic he created called “The Green Turtle” in the 1940s.

Chu was a true Asian American. He was born in 1897 in Kapa’a on the island of Kauai, part of Hawaii (at the time a territory of the U.S.). Chu moved to Chicago, Illinois, in 1919 to study art at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, where he met and married Helga, a Danish immigrant. In addition to pursuing a career in fine arts (visit the blog Chinese American Eyes for images of his watercolors), he also worked as an inker for Marvel Comics. He was one of a small group of Asian Americans working in comics—some for Will Eisner’s studio, some for Marvel, and for other comics companies.

In 1944, Chu created The Green Turtle for Blazing Comics. He wanted a Chinese American hero; his editors insisted the hero be White, for they said American comics readers wouldn’t buy a comic with an Asian hero. Remember the time, 1944; the U.S. and its allies were fighting the Germans in Europe and Japan in the Pacific Theater. As Jay relates, Chu rebelled against his editors by never showing the Green Turtle’s face–he always drew him with a mask on, or covered his face with the Turtle’s cape, or with his punching arms obscuring his facial features. That way, Chu could always think of his character as a Chinese American. When Yang discovered the Green Turtle, he wanted to give him a proper origin story, and this became “The Shadow Hero.” Yang and Liew portray their young protagonist, Hank Chu, as a Chinese American teen whose mother wants him to become a superhero.

“The Green Turtle” lasted only five issues and then faded into obscurity. Incidentally, author Gene Luen Yang collaborated with artist Sonny Liew to create “The Shadow Hero” in 2014. This book offers the origin story for Chu’s Green Turtle. Yang also included an afterword in which he discussed Chu’s work and included some pages of the old comics.

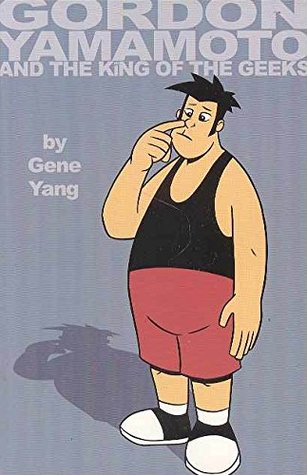

During the decades after World War II, most portrayals of Asians pretty much matched the negative stereotypes created by White American comics creators. Happily for us, the past quarter century or so has seen many AAPI professionals involved in producing comics, and many more positive AAPI comics characters. I remember finding “Gordon Yamamoto and the King of the Geeks” by Gene Luen Yang back in 1997; I loved this comic for showing a non-stereotypical Japanese American. Gordon is big, kind of overweight, and he’s not an honor student. In fact, he’s a bully, who finally learns some tough life lessons. So I’ve been a Gene Luen Yang fan since long before he won the Michael L. Printz Award in 2007 for “American Born Chinese.”

Other great books dealing with different aspects of being Asian American include “Almost American Girl” by Robin Ha, which portrays her immigration experience when in her teens; “The Magic Fish” by Trung Le Nguyen, in which he uses several fairy tales from different cultures to show how he dealt with his sexuality; and George Takei’s “They Called Us Enemy,” about his family’s experience in the relocation camps during World War II.

Now, readers can find plenty of AAPI superheroes, including Ms Marvel, Silk (from the Spider-Verse), and Shang Chi (who will soon have his own movie), as well as many other characters in fantasy, science fiction, domestic drama, and humorous fiction written and drawn by creators whose families came from all over Asia, South Asia, Southeastern Asia, and the Pacific Islands.

AAPI comics contributors have given us themes unique to the AAPI experience, introduced us to multifaceted, complex characters (which have hopefully helped us to move beyond one-dimensional stereotypes), and created characters whom we can all relate to and be inspired by.

Brodart customers can search Bibz to find many of the creators, characters, and books I’ve mentioned.

Further Reading:

Asian Representation in Comics: Who does it best, East or West?

Bring on the Spam Musubi: The State of Asian Representation in Comics [Roundtable]

Unmasking Identities: Superhero Representations of Asian Americans in Graphic Narratives (Free PDF download)

Positive Asian Representation in Comics Matters

Chinese American Eyes: Famous, forgotten, well-known, and obscure visual artists of Chinese descent in the United States

If you’re looking for a graphic novel guru, you’re looking for Kat Kan. Kat looks like the stereotypical librarian with glasses and a bun, until you see the hair sticks and notice her earrings may be tiny books, TARDISes from Doctor Who, or LEGO Batgirls. Click here for more.